Lies, Damn Lies, and Advertising

After I graduated from university, I visited two of my childhood friends in Bristol. We hadn’t seen each other in a few months, so at the time we treated the visit as somewhat of a reunion. Naturally, we quickly got into sharing our plans for the future. It was time for us to all start our careers and become serious people. Having studied Psychology, one friend was pursuing education. The other shared a love of film with me and looked to television as a way into the industry.

“You’re going into film too, aren’t you, Thom?”

“No. I want to work in advertising.”

Stunned silence.

"But, why? You love film. Advertising? They’re a bunch of liars.”

This was back in 2006 and not a lot has changed since then in terms of people’s perceptions of our industry. Research by Ipsos Mori ranked advertising executives as the least trusted profession in 2021 (only 16% of people surveyed generally trust us to tell the truth), narrowly behind Politicians and Government Ministers.

Believe it or not, people’s opinions of us had actually improved since they last conducted this research, up from 13% the previous year.

This research was in no way isolated, nor did it reveal something we hadn’t known for some time. 60 years of survey data acquired by the Journal of Public Policy & Marketing had consistently indicated that about 70% of consumers think that “advertising is often untruthful, it seeks to persuade people to buy things they do not want, it should be more strictly regulated, and it nonetheless provides valuable information”.

There are numerous factors affecting this opinion of advertising and advertising executives. Referencing the 60-year study, Tom Roach alludes to events that have captured attention culturally, perhaps confirming existing biases within the general population.

“Distrust in advertising is likely pretty constant. 50s scares driven by people like Vance Packard are similar to more recent micro-targeting scares (Cambridge Analytica etc).”

Part of Tom’s point is how these events have shaped people’s opinions of advertising in general, but the other aspect of this focuses on people’s perceptions of the media or channel in which advertising is observed. The Cambridge Analytica scandal reinforced people’s concerns around the use of their personal data by large corporations, but more specifically, the fear that tech companies could be easily weaponised by hostile state actors. There was likely a halo effect from this perception that data was being used maliciously, or at least in a manipulative fashion to persuade the masses towards holding views or taking actions that they would not naturally do of their own accord.

A recent Ipsos survey released by The NEW INSTITUTE in Hamburg, Germany shows that trust in the internet is driving audiences to demand policy change.

“There is growing global desire by individuals to protect the access to and use of their online personal data, not just for privacy but also to improve direct benefits to individuals and expand positive societal outcomes.” - Dr. Paul Twomey, Initiative Lead at THE NEW INSTITUTE

“There’s little doubt that we are witnessing a steady global erosion of user trust in the Internet. And that skepticism is being driven by concerns about data privacy and security” - Dr. Fen Hampson, Visiting Fellow at THE NEW INSTITUTE and a Chancellor’s Professor at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada.

The Edelman Trust Barometer mirrors this fear of big tech, with perceptions of technology companies declining dramatically over the last 10 years. Strangely, perceptions of financial services have improved. We’ve forgiven the bankers, apparently. Well, let’s see how long that lasts now they’ve got their bonuses back.

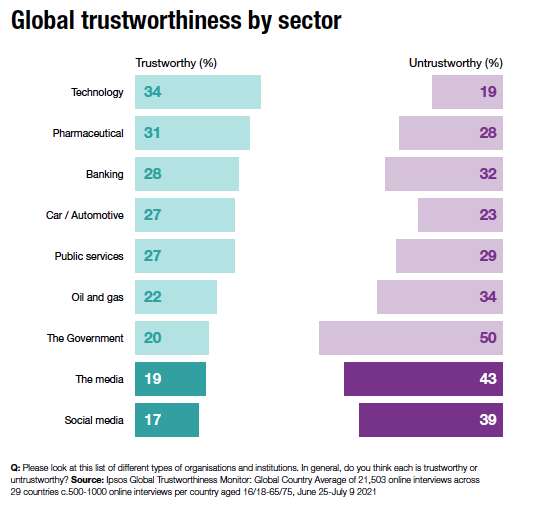

Coming back to the point on channels, Ipsos research confirms that there is a growing mistrust of social media companies and the media in general. This may relate to events like Cambridge Analytica and Brexit, Trump and Russian election interference, or the simple fear that personal data is being used maliciously. Whatever the reason, it’s clear that people do not trust these channels as much as they once did, and as such, our work may suffer from those associations.

“The UK mass media is also one of the least trusted in the world, according to the Edelman barometer. We’re a nation of bullshitters & everyone’s fully aware.”

Perhaps Amy’s right about us being bullshitters. It’s what the Ipsos research suggests too. People have formed quite strong opinions on what advertising workers actually do.

People don't trust ad execs because:

They are paid to tell one side of the story

They lie or bend the truth

They promote unnecessary consumption

That is quite hard to read but hardly surprising. Are they wrong about us?

Regardless of whether these views are true, or whether declining trust in the channels or platforms we use is having a halo effect on us, it is clear there is a broader decline in confidence towards our clients. This Gallup research marks a direct decline in confidence towards ‘Big Business’ from the beginning of the era of social media until now. However, confidence and trust are different things and perhaps matter in different ways.

“The variance between promises and actual behaviour of corporations has never been wider - they say we’re in this together but only ever work for shareholders...thus the behaviour of clients makes us liars.”

Tom Roach explores this disparity between what brands talk about and what they actually do in his blog Brand Purpose: The Biggest Lie The Ad Industry Ever Told? In it, he breaks down brands being ‘purposeful’ into three groups:

1. Brands that are Born Purposeful - I referenced this group myself in my own blog In defence of brand purpose. These are the brands often referenced in industry reports on purpose. Toms, Ben & Jerry’s, Patagonia. They were all founded by activists so their values and purpose have always been clear from the outset. It would be odd in fact if they didn’t campaign in a purposeful way. I think this is the group of brands that appeal most to ad workers who feel affected by their friend’s negative perceptions of what they do, or research like the Ipsos.

2. The Corporate Converts - Tom defines them as “often larger businesses which have adopted the concept of purpose more recently. They usually seem to genuinely want to make a positive difference to the world alongside making money, sometimes to correct past wrongs or just to become a better corporate citizen.” Unilever now works from a purpose model for each of its brands to demonstrate how and where the brand may influence my family, my community, and the wider world. I think this kind of approach still ladders from the product and the customer value proposition, so they’re thinking can stretch naturally while still keeping their feet on the ground. As such, I don’t personally take issue with this.

3. The Pseudo-purposeful - These brands on the other hand are where things have just gone wrong. As Tom writes, “These are the ones for which purpose is just a new ad campaign claiming to try and solve an issue like gender or racial equality, or toxic masculinity or whatever the most resonant topic is that their social listening data says is trending with their demographic that month.” As I mentioned in the first group, I think this is where disgruntled ad workers are clumsily affecting their own personal agendas on their client’s business, or infecting the marketing plans of ambitious clients with false or misleading promises.

While this is going on, is it any wonder that normal people look on in bemusement? But it isn’t just the phoniness of pseudo-brand purpose work that is affecting perceptions of the advertising industry. There is a larger issue about the work simply not working the way it is meant to.

As Richard Shotton pointed out to me, it is less about trust being in decline. In fact, other research by the AA suggested that trust in advertising wasn’t actually in decline (despite them indicating as such).

What was actually in decline was favourability towards advertising. This is more worrying, and I believe this relates more to the wider issue of confidence in business declining. As ultimately, it suggests our ads simply aren’t working the way they should be.

This is a story mirrored recently by Peter Field, who wrote in his 2019 WARC article The Crisis In Creative Effectiveness, “The most recent IPA/WARC Rankings data, explored in the new Crisis of Creative Effectiveness report, confirms this continuing decline; creatively awarded campaigns are now less effective than they have ever been in the entire 24-year run of data and are now no more effective than non-awarded campaigns. We have arrived in an era where award-winning creativity typically brings little or no effectiveness advantage.”

This decline in creative effectiveness is largely driven by short-term thinking. Shifting to promotional comms and away from longer-term brand-building. He adds, “Creativity delivers very little of its full potential over short time frames.” While it is true that the commercial focus of advertising has shifted, the effect on the kind of creativity we are employing has shifted too.

As we’ve seen, there has been an increase in brand-purpose-led work, and award shows have chosen to reward this approach. This reinforces the industry perspective that this is the right thing to do for our clients. The net result is we’re taking ourselves a lot more seriously now. Far too seriously.

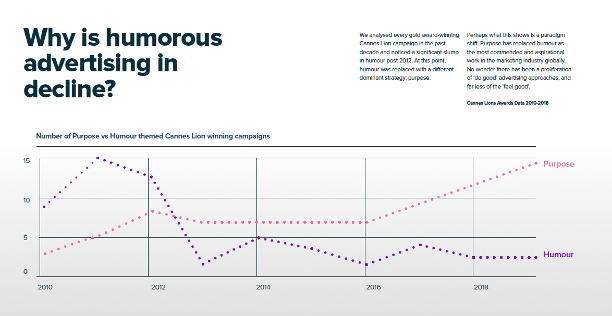

Research by BMB showed the growth of purpose-led work at Cannes was at the detriment of humour-led creative. What judges deem award-winning has changed.

The growth in purpose-led creativity comes at a cost to entertaining formats.

The story we see at the award shows is reflected more broadly across the industry as a whole. Ads that entertain, in particular, ads that make people laugh, have been in decline for some time.

The other effect of award shows encouraging pseudo-purpose-led work through awards, is we’ve encouraged the rise in fake award cases.

Echoing our audience’s opinion of us as self-motivated and greedy, fake award cases have been a major issue at award shows.

“Grey Singapore’s notorious I See App, which purportedly crowdsourced images of the sea to spot refugees in distress but turned out to be fake, have brought this issue into the spotlight. Grey was forced to return the bronze Lion it won for the app in 2016.” - Campaign Magazine

We spend a lot of our time talking about how important it is to know our audiences, to get out of our industry bubbles and create meaningful work that people actually like. With that in mind, we should probably consider the Ipsos research again and what exactly it is that people want from advertising.

To create interesting and entertaining ads

They are self-motivated and greedy

They are annoying and arrogant

Well, having worked in the industry for over 15 years, I can say at least two of those things are consistently true, the other is certainly true sometimes, but not as often as it should be. The first point is quite telling.

Looking more directly at research into the types of ads that appeal to audiences the most, the story of brands as entertainers gets stronger. “Make me laugh and entertain me” resonated the most with US consumers when they were surveyed this year.

It’s worth noting that the cultural context of almost endless existential dread may be helping to amplify this desire for escapism, but perhaps it is simpler than that. People want brands to entertain them more and preach to them less.

“We should accept it as an immutable fact and try to entertain people instead.”

And that’s no bad thing. The top two results from the survey above leave an enormous amount of space for creative to explore. Perhaps we take this moment to rethink our role in broader culture and use this as a rallying cry to rediscover love for our craft? Free ourselves from the self-inflicted pressure to change the world or solve problems that aren’t ours to solve. Get back to just having fun and helping brand grow.

And it doesn’t have to be the case that everything has to be funny now. Obviously there is a time and a place for humour. But we used to find other ways to entertain and to be memorable.

“Personally, I think the only ad tactics people trust are jingles. The catchier the jingle, the greater the consumer trust.”

There’s a lot to digest here.

On the one hand, different measures of trust appear to tell a story that we as individuals working within advertising aren’t particularly liked by the outside world. That some of the channels we operate within which we have been continuously shifting budget toward over the last decade or so are now facing a crisis of trust. That there is a deepening disconnect between what we believe to be important or award, and the honest expectations our audiences have towards our creative output.

Most people I have spoken to about this were indifferent to the negative outside perspectives about us. I understand this point of view. If we just focus on the effectiveness of advertising and what actually matters to the work, then trust isn’t a measure worth paying attention to. It seems irrelevant to us. The measure we should be paying attention to is favourability towards our ads as this is more directly linked to creative effectiveness.

However, if we take off our advertising hats for a moment, step outside are commercial bubbles, and start behaving like empathetic human beings who care about what others think of us, then this is a problem. If we have any hope for the future of our industry and that we will continue to be considered an exciting creative industry for new talent considering a career in advertising, then I’m afraid I don’t feel indifferent at all. As the co-founder of our industry’s first union, I feel compelled to fire a warning flare at this point. It can’t be the case that an industry I love and cherish and have spent my entire career growing within and championing externally, is apparently perceived as being stacked full of liars. During a crisis of trust in media and governments, I do not want us to be thought of in a similar vein. The crises in those parts of society are deepening and represent at least a perception that things are fracturing in violent ways. We can’t find ourselves mentioned in the same breath.

I believe we need to refocus efforts on appealing to audiences in a meaningful way and do so by making brands far more entertaining. Far less serious. Far more fun.

During the pandemic, I attempted to evangelise this idea to our community, and I genuinely thought others would recognise the need for escapism through culture, and the huge opportunities for us to play a part in offering value there. But not much happened. Barely a joke was told. Instead, we were constantly reminded of how terrible things were in ads featuring sad piano music and empty claims of “we’re here for you”. And it wasn’t just one or two of these worthy, painfully dull ads. It was practically all of them. A pathetic wallpaper of meaningless drivel reminding the world that the world was utterly shit. Good lord.

The outside world doesn’t require a parallel tone to be adopted in culture. It’s no coincidence that the golden age of Hollywood happened during the Great Depression. People don’t want to see their pain reflected back at them. And why the hell would they? It’s painful!

My hope is that this challenge to be more fun, more entertaining, and less serious will be a lightning rod to creatives in our industry.

But if we continue to fail to make people like us, then we can always fall back on our other job playing piano in the brothel.

“Don’t tell my mother I’m in advertising – she thinks I play the piano in a brothel.”