What is the stretch?

Change is a constant. A universal law. All barriers will crumble, and all empires will fall.

The inevitability of change isn’t in question. What should be in question is what is the right change, how big or small should it be, and how fast can it happen?

We are in the business of change. We sell it, craft it, and if all goes to plan, we make it happen. In the discipline of strategy, we aim to present change in simple forms, taking complex systems and entities and framing what needs to happen to them for them to be more successful.

Typically in communications, this will include making people think differently about a brand or product because they show little interest in it or simply don’t think of it enough. Other times we might need to improve an experience of a product or brand from a bad one to a good one, and so on. Whatever the shift required, it is usually framed as moving something from one position to another. A From > To. A simple framework designed to make change seem simple.

Change needs to seem simple in order to sell the change itself, as opposed to the change being simple. Change may be thought of then as a political tool, as opposed to an operational process. My issue with this is too often change is presented as certainty. While this ensures budgets get spent, it does little to detail the mechanics of change itself.

I propose evolving our From > To framework for change by asking questions about the shape of change, and more critically, defining how much of a stretch these changes will require.

Where are we now?

To define where we are going, we need to know where we are starting from.

A current state analysis is bread and butter for strategists, and I don’t feel there is great deal to say about it, other than the necessity of being clear on the most important areas requiring consideration. I typically favour the 3C model, as it focuses our thinking on three critical factors without becoming overly complex or unwieldy for onward communication. Remember, you need to convince others of your findings and hold their attention. You can’t persuade people who aren’t following your train of thought. With that in mind, we set out to ascertain the foundational realities of our customers, our company and the category we inhabit.

“Reality” is perhaps the most important word to consider throughout this process. Mark Hadfield of Meet the 85% framed his own agency’s approach around this mantra, “We exist to deliver reality in an industry that is brand-centric.” Mark’s point on research being brand-centric is a harsh but necessary truth. If we’re not careful, we will only focus on the things we think we know and look close by for things that confirm our suspicions. When in reality, there may be important observations sitting outside of our sphere of knowledge, or as Donald Rumsfeld put it, “there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know.”

We should focus more energy here, conscious that everything else tends to be heavily weighted toward confirmation biases.

Where do we want to be?

Defining the destination of change is the real work. These are the intended strategic shifts that will take place if we do what is necessary to accomplish them. I won’t spend time talking about the possible directions these may take, as that is fundamentally what strategic thinking is all about, and frankly, enough has been written already about that. What I would like to talk about is how we frame these shifts and how realistic they truly are.

In order to do so, let’s think about the idea of The Stretch.

This is ridiculously simple, but often overlooked.

How much of a stretch will this change be?

Is the distance between where we are and where we want to get to realistic?

Can it be achieved through these changes?

If a proposed change is too much of a stretch then the theoretical band between the current and desired future state will snap. When this happens suspension of disbelief collapses. In any magic trick, you need people to suspend disbelief.

In any change, you need people to believe it is not just possible, but realistic.

If we are developing new creative for a brand people have strong established associations with, then we need to consider the stretch we are asking people to make.

All of those memories, associations and preconceptions are loaded into the current state and can stretch only so far towards our proposed new reality. We can’t stretch too far and risk these breaking. These connections form the foundations on which we build the brand.

I would argue that the greatest crime brand managers commit is forgetting what built their brands originally, and venturing far beyond a reasonable stretch in search of personal fame. This is a grave error. People need anchors. They need connections to known things to place themselves and rationalise what they’re seeing or hearing.

The unfortunate truth is that this is not a short-term game. These smaller, realistic stretches when layered on top of each other will span decades, far beyond the average tenure of a brand team or agency relationship. That is, they would do if these teams consciously and effectively built brands in this way.

But the sad reality is, more often than not, we favour short-term reactionary and tactical thinking. We reinvent brands too quickly with overstretched creative and strategic choices and as a result, we forget the anchors and foundations that are the brand’s true source of power.

We must consider how much of a stretch our future state envisions and if we can make it in one go, or if achieving this change will require multiple smaller stretches over time.

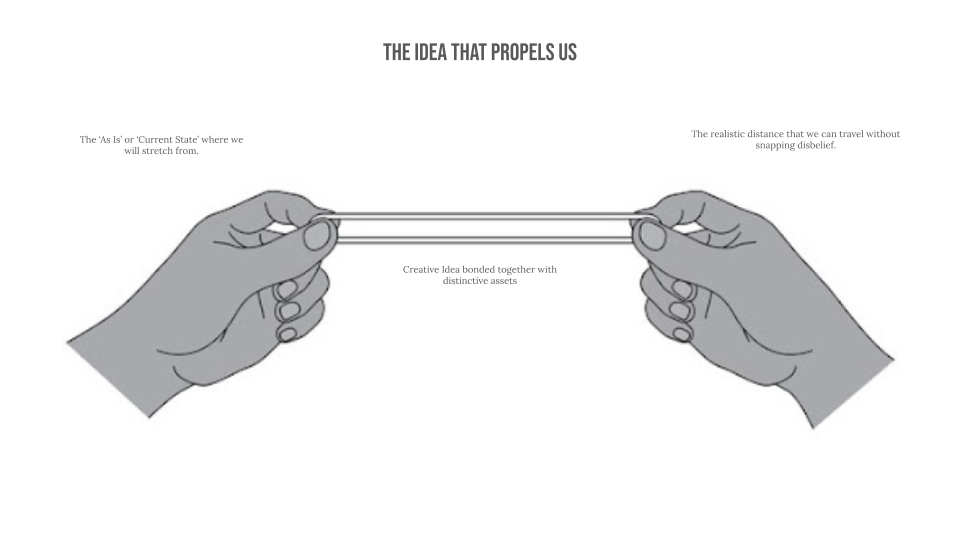

The last piece of the puzzle is the change itself.

In the case of communication, this will typically be a creative idea that comes to life across various channels. When we think about the connective tissue within the stretch, we can think broadly about two areas. The idea itself and the distinctive brand assets which help wrap the idea and connect it back to the brand. Distinctive assets are bonding agents. They bond an idea to a brand.

Without effectively using distinctive brand assets, the band we are stretching breaks. As a result, people don’t make the connection and fail to recall who made the communication or associate the brand with the idea.

All of these things are therefore delicately balanced and require careful consideration in both the conceptualisation of the idea, the craft of the execution and the use of distinctive brand assets.

We can think about this balance through the following questions:

Is this idea the kind of idea people would expect of the brand? Does it feel like a stretch the brand can make?

Are distinctive assets bonding the idea to the brand effectively without distracting from it?

Will the idea stretch the brand towards the desired future state?

All of these questions and more help evolve our understanding of communication as a tool for change. Considering what needs to stretch and how much of a stretch is required (and realistic) grounds creativity within a clear strategic model.

I genuinely believe this way of framing change helps anchor strategy and creativity together while helping brand owners think longer-term about their brand plans.

This framework aims to remove short-term thinking and to see brand building as an iterative process.

Next time you’re thinking about the journey you need to take a brand on through communications, consider asking yourself how much of a stretch is needed.